By Angela Dufour, MED, RD, CSSD, IOC Dip Sports Nutr, CFE & Melissa Allan, Dietetic Intern, MSVU

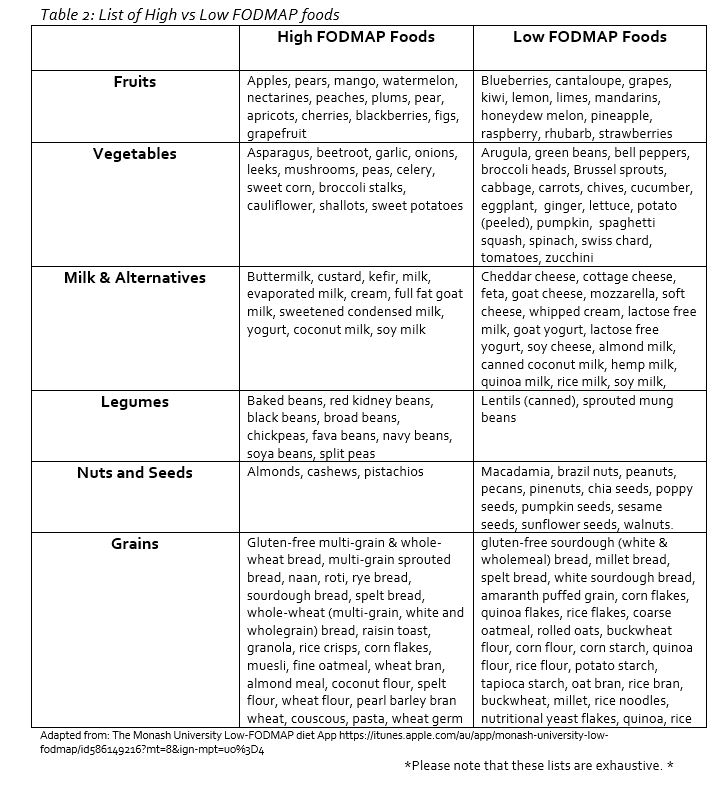

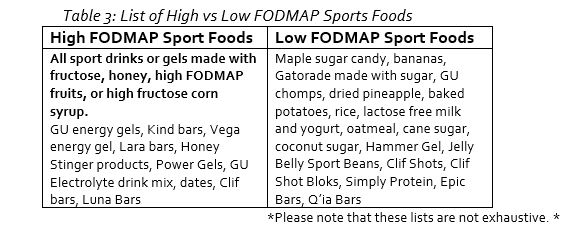

Beets, apples, garlic, onions, sourdough, rye, dairy, bananas, almonds, coconut water, and orange juice. You just read a great list of healthy, nutritious foods which every athlete should incorporate into their daily training diet, but what is the common denominator in these foods that may cause some athletes to be avoiding them? FODMAPs. Foods that (See Table 2) contain poorly absorbed, rapidly fermentable carbohydrate molecules are known as FODMAPS, and they may cause gastrointestinal (GI) pain and discomfort after eating for some athletes.

What are FODMAPs?

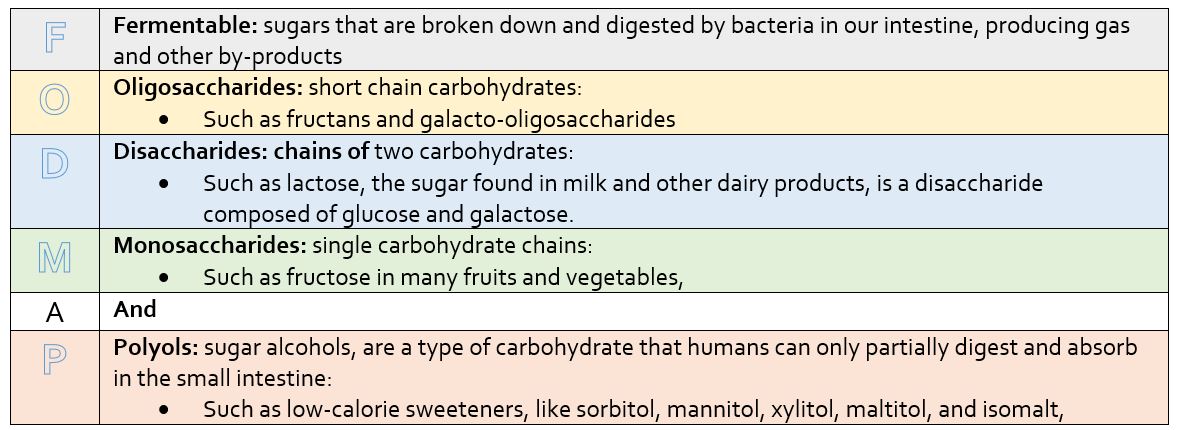

FODMAPs stand for the types of sugars in foods that contain small-chain carbohydrate (sugar) molecules, which are poorly digested and absorbed in the small intestine of most people with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). These poorly digested sugars are then fermented by bacteria, producing gas3. The term FODMAP is the acronym that represents the five different groups of fermentable carbohydrates:

Adapted from www.CDHF.ca: Understanding FODMAPs

Globally, around 11% of the population are affected by these symptoms, meaning that there are athletes who may experience disrupted training, decreased performance, added stress, and a lowered quality of life1. The symptoms are the result of a poor functioning GI tract, a disorder called Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS).

IBS

IBS is a chronic and reoccurring GI disorder that typically includes symptoms like abdominal pain, bloating, extreme flatulence, distention, and altered bowl movements, i.e diarrhea and consitpation. Diagnosis is dependent on the athlete’s history of symptoms and a certain set of criteria3. The cause is still unknown but there is evidence to support that there are multiple factors involving changes to the gut4 , such as; abnormalities in motility, infections, exaggerated stress affecting the brain-gut interaction, and gut hypersensitivity5.

There is currently no known cure for IBS, thus it is important to try to adjust an athletes’ diet to control or reduced the symptoms.

The low FODMAP diet

STAGE 1: The first stage involves the removal of all high FODMAP foods from the diet for eight to ten weeks. All high FODMAP foods should be replaced by low FODMAP foods.

STAGE 2: After eight to ten weeks of TOTAL elimination of high FODMAPs, the reintroduction of some high FODMAP foods can begin one at a time in gradual amounts until symptoms return or a proper portion size is reached7. Start by Introducing a food that the athlete has really been missing or that is an important food providing nutrients that help benefit their training, performance or recovery.

Does the low FODMAPs diet work?

A systematic review done in 2015 on 22 different studies showed that scientific evidence supports the theory that adherence to a low FODMAP diet can improve the overall symptoms of IBS8 and improve quality of life8. Athletes need adequate nutrients in adequate amounts and timing for available energy and to limit fatigue and promote recovery. With the careful implementation of a low FODMAP diet an athlete with IBS can be assured that performance with limited or no GI symptoms can be obtained while still being able to meet their high energy and nutrient needs.

The Bottom-line

Talk to a registered dietitian and/or other healthcare professional to provide guidance on a low FODMAP diet and other methods that can help with IBS symptoms. Your athlete may want to keep a food and symptom journal for at least 3 days before starting the low FODMAP diet allows for the comparison of changes in symptoms once the diet is started7.Gastrointestinal issues and diseases play a major part in the lives of many athletes. With the help of a low FODMAP diet, the symptoms that plaque their lives and performance can be vastly improved, helping them to compete to the best of their ability.

References:

1. Canavan, C., West, J., & Card, T. (2014). The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clinical Epidemiology, 6, 71–80. http://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S40245

2. Patel, E. K. (2017, March 28). Cut out FODMAPs, cut out IBS symptoms? Retrieved June 02, 2017, from https://examine.com/nutrition/cut-out-fodmaps-cut-out-ibs/

3. Department of Gastroenterology. (n.d.). The Monash University Low-FODMAP diet. Central Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. http://www.med.monash.edu/cecs/gastro/fodmap/

4. Sinagra, E., Pompei, G., Tomasello, G., Cappello, F., Morreale, G. C., Amvrosiadis, G., … Raimondo, D. (2016). Inflammation in irritable bowel syndrome: Myth or new treatment target? World Journal of Gastroenterology, 22(7), 2242–2255. http://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i7.2242

5. Lee, Y. J., & Park, K. S. (2014). Irritable bowel syndrome: Emerging paradigm in pathophysiology. World Journal of Gastroenterology: WJG, 20(10), 2456–2469. http://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i10.2456

6. Canadian Digestive Health Foundation. (n.d.). Understanding FODMAPs factsheet. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology. http://www.CDHF.ca

7. Dietitians of Canada. (2016). The low FODMAP diet: Healthy Eating Guidelines. PEN: The Global Resource for Nutrition Practice. http://www.pennutrition.com.ezproxy.msvu.ca/viewhandout.aspx?Portal=UbY=&id=J8HqWAI=&PreviewHandout=bA

8. Marsh, A., Eslick, E. M., & Eslick, G. D. (2015). Does a diet low in FODMAPs reduce symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders? A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Nutrition, 55(3), 897-906. doi:10.1007/s00394-015-0922-1